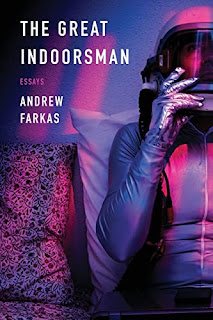

Andrew Farkas is the author of the collection, The Great Indoorsman: Essays (University of Nebraska Press), of which Kathleen Rooney writes, “with searching rumination and exquisite comic timing, Andrew Farkas takes readers on a sublime tour through dive bars and coffee houses, video shops and casinos, pool halls and motels room, dilapidated movie theaters and dying malls.” Farkas is also the author of several works of fiction including The Big Red Herring, Sunsphere, and Self-Titled Debut. He is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Washburn University.

Farkas will be the featured reader at the Final Thursday Reading Series on April 27 at the Hearst Center for the Arts in Cedar Falls, Iowa. The in-person open mic takes place at 7:00 p.m. and Andrew Farkas takes the stage at 7:30. Farkas’s reading will also be simulcast on Zoom. Click HERE to register for a Zoom link.

Interview by Jim O’Loughlin

JIM O’LOUGHLIN: You were initially scheduled to visit Cedar Falls in March 2020 before the pandemic upended all of our lives. I appreciate that you helped the Final Thursday Reading Series pivot to digital with an online reading, and I’m glad we’ll be able to have a new ending for that narrative when you actually appear in person. But I’m wondering how the pandemic impacted you as a writer in either your subjects or habits.

ANDREW FARKAS: I was very lucky that, when the pandemic started, I was already fully immersed in a project, that being my book The Great Indoorsman: Essays. Quite a few people think the book is about the lockdown time period, but it isn't. Instead, it's about (or one of the things it's about) is my love of indoors spaces. Since I couldn't go anywhere, thanks to Covid, I was able to visit all of the places I missed in my mind by writing about them. Once I finished The Great Indoorsman, I realized I had another book that was partially done: Movies Are Fine for a Bright Boy Like You: Stories. I admit, however, by this point I was feeling worn down and wasn't able to progress through that book quite as efficiently, seeing as how I just finished it recently (I think). I did try, briefly, to start a brand new project, but found I just wasn't able to get it off the ground because of the general malaise. No matter what, I kept working at writing. But the most successful period was early on when I was working on The Great Indoorsman. I guess, in a way, it felt like I was in the pre-pandemic period because I'd started that book beforehand.

JO: I had a similar experience in that the pandemic gave me time to finish up some projects I had started but made it impossible to tackle something brand new. I read a recent interview with you in the Brooklyn Rail (which, to continue the theme, was a cultural lifeline for me during the pandemic with their daily Zoomcast events), and you said you had a “laid-back way with everything, which stems from my absurdist worldview.” Can you talk about how absurdism helps you approach the world around you?

AF: If you accept that there's no inherent meaning in life (or, anyway, that none of us will ever be able to discern the meaning), then, as I see it, our lives and the things that happen to us don't necessarily have to make sense narratively. I therefore find that I'm especially open to the moments in life that are odd because of my absurdist approach. For instance, in The Great Indoorsman I relate a time when, out of nowhere, I heard a guy playing poker say: "Our son died. And the guy we replaced him with was eaten by a bear. He just got in the cage with the bear, and the bear ate him." Later on, other folks would say to me, "I just would've ignored that guy." But I didn't. In fact, long after his story, I kept asking people if they remembered what that guy said. But because it didn't fit into a sleek narrative, because it didn't make sense, they'd all forgotten or thought nothing of it. I guess I'm constantly calling into question the belief that the big things, the things that fit easily into a straightforward narrative are important. That's probably also why the places I focus on in The Great Indoorsman aren't the normally celebrated, beautiful places. Sure, I like those too, but I can find the beautiful and the sublime in a bowling alley just as well as a palace.

JO: What else should readers know about The Great Indoorsman?

AF: Although there is a proud history of outdoorsy literature (Romanticism, the Transcendentalists, etc.), this is the first installment of what I hope will become indoorsy literature. After all, since the book came out, a number of people have approached me and said furtively (always furtively), "I'm, I'm an indoorsperson too." So if you've found yourself hiding (inside, of course), so no one knew your secret, you can come out (but not all the way to the out-of-doors for goodness sakes) and you can declare yourself an indoorsperson and you can read The Great Indoorsman and then, then, you can proclaim, in no uncertain terms, "This isn't how to go about expressing my love for the In-of-Doors at all," because, like, outdoors people probably don't grab the first book ever written about camping to learn about camping since the person who wrote it was likely eaten by a bear, so the reason you go to The Great Indoorsman is to say, "Now I know what not to do," and then you can boldly move forward and provide the world with the next installment of indoorsy literature. So what readers should know about The Great Indoorsman is that it's the first indoorsy book, but hopefully not the last.

JO: Since you've always worked with fiction in the past, what was it like writing creative nonfiction?

AF: Seeing as how a lot of my fiction is metafiction, I thought it was going to be easy (since even when I'm making things up, I'm telling the reader I'm making things up). But I did have to struggle with the constant problem all creative nonfiction writers who aren't famous have to struggle with: why would anyone want to read about me? One way I hope I solve that is by filling my essays with humor. So, if for no other reason, people might want to read about me to laugh at me (and also with me). I also use lots of different kinds of references, meaning I include a great deal beyond myself that readers might be interested in (various films, urban legends, physics, pop culture, etc.). Furthermore, our interior lives are part of reality also. So when I really felt that I needed to invent something to bring an essay together, I used lines like "I think" or "I imagine" and even though what happens next didn't necessarily happen in the physical world, the reader understands it happened in my mind and is now happening in their minds. Since I also knew that I could play with the structure of each essay, I ended up learning that the creative nonfiction genre is very plastic, not rigid the way so many people believe.

.JPG)