Thursday, 19 December 2024

Thursday, 7 November 2024

An Interview with Paul Brooke

November’s Final Thursday Reading Series comes one week early (on November 21) due to Thanksgiving. The featured reader will be Paul Brooke, a Professor of English at Grand View University and editor of Cities of the Plains: An Anthology of Iowa Artists and Poets, which features 57 artists and poets and highlights the immense talent of the state. Brooke will be joined on stage by regional contributors to the collection.

The Final Thursday Reading Series takes place (**don’t forget: one week early) at the Hearst Center for the Arts in Cedar Falls, Iowa. There will be an open mic at 7:00 p.m. (bring your best five minutes of original creative writing). Paul Brooke and friends take the stage at 7:30. The featured reading will also be simulcast on Zoom. Click HERE to register for a link.

Interview by Tomiisin Ilesanmi.

TOMIISIN ILESANMI: “The Cities of the Plains” is a symbolic title. What was the inspiration behind this choice, and what do you intend to convey with this introduction?

PAUL BROOKE: It comes from a poem from Mona Van Duyn and, of course, it relates to Cormac McCarthy as well. But in the poem she writes of "fabulous bouquets of persons" and I immediately thought about the talent pool of artists and poets in the state. It also suggests that we meld the urban and the rural throughout our work. Notice that the cover is the capital with the prairie underneath showing both aspects of the title.

TI: This anthology portrays diverse artistic expressions across Iowa. Was this an intentional setup, or did you experience an organic shift while compiling the project?

PB: It was all very intentional as we have a diverse group of artists/poets and I wanted it to show the cross section of folks who are doing this good work. This also makes the anthology very surprising and gives a wonderful selection of art and poems.

TI: The early poems in this collection challenged my preconceived perception of an “Americanized and stereotypical” Iowan depiction. Can you explain how you addressed those expectations and provided a more nuanced perspective on these themes?

PB: That was purposeful as I wanted the anthology to be multicultural, leaning into interdisciplinary connections. This meant that writers like Vi Khi Noa needed to set the stage. Also, the artwork really helped to explode that "Americanized and stereotypical" label. So many artists are doing ground breaking work that the old convention seems wrecked.

TI: Why are Iowa poets and artists often disregarded or dismissed?

PB: I think there is a stereotype about

Iowa that we are all farmers or some such nonsense. But there is this

amazing pool of talent which I believe flourishes in Iowa because Iowa

gives us the time and space to be super creative and innovative.

TI: What makes the artistic community of Iowa distinct and why do you think it was important to showcase these artists in this collection?

PB: There had not been a poetry anthology like this done since 1996 and it was high time to showcase these artists and poets. It gives all of them a publication, a place to read/present their work, and a way to connect. I have been mentoring many of the poets in this collection and try to invite them to read when the opportunity arises.

TI: As both a contributor and the editor of this project, what did you take away from the experience? What are the benefits of taking on a collaborative project?

PB: I have worked on more massive projects but this is the most rewarding for me since I have helped many young artists and poets. For some of them, this was a first publication. For others, it reinforced their skill/talent. We need more of this in Iowa. We must celebrate each other and support our artists and writers in every way possible.

Friday, 18 October 2024

An Interview with Brooke Wonders

For this special Halloween FTRS event, “A Night of Monsters,” the inmates take over the asylum. UNI’s Brooke Wonders, alongside students in her horror literature course, will be reading new stories of terror and dread. Dr. Wonders’s scary stories have appeared in Black Warrior Review, The Rupture, and The Dark, among others. She is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa and editor of literary horror magazine Grimoire.

BROOKE WONDERS: Do people enjoy the fear, or moving through fear--or both? I'm in the "both" category. I like how horror values intensity of sensation, an aesthetic predilection that has a long literary history: the Gothic influences sensationalist literature which influences pulp fiction. At a psychological level, horror ends. In films and novels, there's a finite point at which the terror is over. That doesn't always happen in real life. Horror consoles us with the illusion of control, and I am a control freak at heart.

JO: As a writer, what has drawn you to writing horror fiction? What does that genre allow you to do that draws you to it?

BW: I love how horror is rooted in the senses and resists intellectualization. Great horror, if you're open to it, circumvents the rational mind; it lives in the nervous system. My writing process focuses on image and emotion. An image comes to me via observation or epiphany, sometimes with an emotion attached. Answering the question, "why and how does this image haunt me?" is how the story comes into being. Horror is particularly well-suited to this process.

BW: I love this question. It makes the choice of fiction or nonfiction into something spatial (distance) and relational (connection). I’m a kinetic writer; I'll go on walks or make faces in the mirror while working on a piece. I feel connected to my unconscious when I write. If I had to describe writer's block, I'd say it feels like disconnection or distance. I begin from image and emotion whether I'm writing fiction or nonfiction; the only difference is, for nonfiction I'm not allowed to make stuff up. But both require me to go to difficult places psychologically, and for the sensations I'm evoking to feel real, they have come from lived experience. If there's any difference between nonfiction and horror, for me personally, I'd say horror feels safer to write than nonfiction because I can conceal more of myself without breaking the reader's trust.

JO: So, you’ve got a plan for Halloween and FTRS! We’ve never done a special event exactly like this before. Without giving away any surprises, can you talk about what your class will be doing and what attendees should expect?

Friday, 20 September 2024

An Interview with Marc Dickinson

September brings UNI English alumni Marc Dickinson back to the Cedar Valley. Dickinson is the author of the new short story collection, Replacement Parts (Atmosphere Press). A UNI English alumni, he teaches creative writing at Des Moines Area Community College and coordinates the Celebration of the Literary Arts reading series.

MARC DICKINSON: The setting is definitely a character in the book, informing the lives of its inhabitants. The fictional town of Dexton is a conflation of several small places in Iowa, but it was particularly influenced by my first teaching position in town whose factory—and main employer—had been shut down. Many laid-off employees came back to college and were in my classroom, and these ex-assembly-line workers—who were replaced by exported labor, who could’ve been bitter about the raw deal—were the most inspiring students I’ve ever had the privilege to teach. They taught me so much through their stories they graciously shared with me.

But the town was hit, economically, which inspired the fictional town of Bridger—a neighboring town with a similar status, until a new highway is built—and all the money, infrastructure, and jobs funnel from Dexton to Bridger. It’s a common kind of rural gentrification, wherein a seemingly small town gets absorbed by urban sprawl. A place that once had a single gas station becomes an affluent city that no native citizen can afford—while other small towns bear the brunt of being left behind.

GT: I’ve known you for over twenty years. You’re a well-read, articulate man. A champion of the humanities and profoundly aware of the human condition. But, what I admire about your characters is the dignity with which you present vulnerable, somewhat lost souls. What is it that compels you to tell the stories of those who can’t fully understand or act upon the forces that shape their lives?

MD: Once again, it’s partly due to my experience teaching with working class students, a community that often gets overlooked, made to felt replaceable/expendable—or they’re turned into stereotypes. But all I saw was some of the best of humanity in them. Despite hardships, they never saw themselves as victims. Yet, whenever I read about “lost souls,” especially in blue collar culture, they’re often presented as angry, ignorant, or even extremist.

Also, we often talk about change or transformation when it comes to a character’s climax. And I think that is necessary—everything should head toward change since it’s what gives the story its stakes. But how this manifests itself is complicated. I tell my students to think more along the lines of turn or shift, as opposed to change—a word that’s always too big to hold onto when drafting. And sometimes what manifests is no change at all—but this can be equally unexpected, full of an urgency that can feel transformative in its own way.

GT: I’m impressed with the authentic inner lives of your stories: from the sensibilities of army veterans and reflections on their time in the Suck to an old man working an assembly line to adolescents holed up in a group home to a county sheriff working the first watch in a small town. Tell us a bit about your research process.

MD: I love research, but it’s also dangerous because not everything can go in the story—otherwise it’ll feel like a Wikipedia page. I have to have a bit of a blind spot when I do formal research—I want information but only the right information that moves me. I want to get the details right, but insignificant details clutter up a story. I always look for a detail with a story buried in it.

Often talking (or rather, listening) to people is the best form of research, because when they talk about their jobs, for instance, they always tell it in the context of a story. For instance, when I talked to my neighbor who’s a cop, he’d begin with “One time on patrol…” and then a story is presented to me, full of only significant details that inform, enhance, or maybe even become the essence/point of the story itself. It’s about finding the right detail that reveals.

GT: Your title story, “Replacement Parts,” has faint echoes of Charles Baxter’s “Gryphon.” Maybe, I’m wrong about that, but I wonder if you might talk about ways in which a writer can use scaffolding from other stories to take things in bold, new directions. Your sentences and stories are so well-crafted. Pick a favorite story in Replacement Parts and share with us revision strategies (macro and micro) you used to get the story to the point where you could let it go into the world.

MD: Revision is my entire writing life. For me, drafting is quick, skeletal, full of wrong notes and turns. clutter and cliche—I’m just trying to survive the story, trying to find the spark. And sometimes I never do, which means no amount of revision will help, either it doesn’t speak to me, is just an interesting premise and nothing more—or maybe it just isn’t my story to tell.

But if there is a spark, fanning the flames takes months, if not years, of steady revision. For instance, the title story (which had a different title until the last minute, speaking of non-stop revision), I started years ago, in my MFA (the only story to survive the program). Then I revised it for years and got it published. But if you put it next to the draft in the book, the bones are there but it’s almost an entirely different story, even after I placed it in a magazine.

I love the voice of the young narrator so much—it’s probably my favorite story in the book (which is why it was got the title), but it never felt fully realized because the two main characters, both in elementary school, never interacted beyond Q&A, or exposition, or small talk. There were so many flat moments, no energy, and as you say, I was probably copying too much Baxter for my own good.

So, I cut it in half and made the kids interact more, telling their stories through play, wherein our narrator starts to learn things, make choices, question authority. Soon, there was more urgency, more action, more at stake. Their conversations became mysterious but more meaningful as the relationship grew. As a result, the ending—which never changed—held more resonance. And our narrator, who now had more agency, does transform—even if the last image shows him doing the opposite.

Friday, 23 August 2024

An Interview with (and Book Launch by!) Iowa Poet Laureate Vince Gotera

JIM O’LOUGHLIN: This is the first time I’ve interviewed you since you were named Iowa Poet Laureate. First, congratulations! Second, if wonder if this appointment has impacted your writing or the way you think about your role as a poet?

VINCE GOTERA: Thanks! My main message as Iowa Poet Laureate is that poetry can be fun. Many folks think of poetry as something hard to figure out, something that isn’t accessible, maybe like calculus or trigonometry. I’ve even had people say to me, “poetry is a lost art” ... uh, hello, I’m standing right here in front of you, not lost! Anyway, for decades, I’ve championed light poetry. I think some poets think poetry should be serious, weighty, dark even. Obviously, there’s merit to that viewpoint, but it shouldn’t be exclusive. The great poet Lucille Clifton was one of those who felt poetry can be fun, and she said so on a number of occasions. But at the same time, she wrote very serious poetry as well on, for example, race relations, feminism, and against child abuse. So poetry, in my view, can legitimately live on a spectrum from light to heavy, and it should. My poems in Dragons & Rayguns span that entire spectrum.

JO: There was a time when it would have been considered unusual (and maybe a little outrageous) to publish a collection of speculative poetry, but that’s what you are doing in Dragons & Rayguns. One of the things I love about this collection is the way you use demanding and sometimes intricate poetic forms to write about themes out of popular culture. Does that seem like an unusual juxtaposition to you, or do those high/low culture divides loom less large now?

VG: Well, this would depend on what literary circles one frequents. Those who think of poetry in elitist terms differentiate between “literary poetry” and “genre poetry,” assuming that genres like science fiction or detective fiction, etc., are less important, less accomplished, less difficult. I think such elitism is just bunk. As you suggest in your question, the divide between so-called high and low culture has been breaking down for quite a while, and it’s no longer unusual or outrageous for poets to write speculative poetry (science fiction, fantasy, horror), though, to be fair, there are some literary folks who still look down upon genre literature. I hope Dragons & Rayguns can help to alleviate that situation.

About “demanding and ... intricate poetic forms,” yes, I love to write those, for example, the terza rima haiku sonnet, which I invented in the late 1970s. This is a syllabic form, using strict 5-7-5 syllables, the traditional English haiku shape, without haiku essence per se. There are four of those 5-7-5 tercets finished off by a 7-7 syllable couplet (to add up to the 14 lines expected in a standard sonnet). At the same time, it’s a rhymed form, employing terza rima, the Italian rhyme scheme used by Dante in The Divine Comedy: tercets with interlocking rhyme: aba bcb cdc, etc. The terza rima of my sonnet form is similar to Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind,” aba bcb cdc ded ee. Since the lines are pretty short overall, I often use slant rhyme to make the rhyming more subtle. Actually, this is true of my use of rhyme in general, á la Emily Dickinson, Wilfred Owen, Marilyn Hacker, among other model poets.

Quite a few of my formal poems in Dragons & Rayguns are light poetry ... slapstick, even. A good example is my poem “Sestina: Dragon,” which uses dragon as the repeating end word, with some variations. In formalist circles, this approach is reminiscent of “Sestina: Bob“ by Jonah Winter (in fact, my title is intended to allude to this poem). Less well known but equally inspiring for my poem is my former student Nate Dahlhauser’s parody “My Love of the Sestina,” which uses the word sestina as its single repeating end word. In my blog, The Man with the Blue Guitar, I feature Nate’s poem, which he wrote in one of my creative writing classes. Check it out ... it’s brilliant, fun, and funny.

Speaking of my blog, you’ll find many of my formal poems there (along with free verse, of course), especially during the month of April, when I write a poem a day during National Poetry Month. Some of the poetic forms that appear in Dragons & Rayguns include abecedarians (ABC poems), hay(na)ku (123 poems), concrete poems, and many other forms, especially curtal sonnets, a short sonnet type invented by Gerard Manley Hopkins, another of my model poets.

JO: You were the editor of a speculative poetry magazine, Star*Line, for a number of years. Did that editorial experience influence this collection, or does your writing and editorial work happen in separate parts of your head?

VG: I became editor of Star*Line in 2017, about a year after I ended my run as editor of the North American Review. I wanted to offer my experience of 16 years running the NAR to the field of speculative poetry and to the SFPA (the international Science Fiction and Fantasy Poetry Association, which sponsors Star*Line). This editorship did affect my speculative writing because of community; it was inspiring to be among so many speculative poets who care so much about the genre. (Two SFPA presidents, past and present, wrote the blurbs for Dragons & Rayguns.) To answer your question more directly, I’m not sure the editorial work affected my writing so much ... maybe the other way? My editing was affected by being a practicing speculative writer, and I was honored for a few short years to influence the ongoing development of the genre.

JO: You often write about figures from Filipino mythology, and some of that work appears in Dragons & Rayguns. What has drawn you to that subject? Were these tales that you knew growing up or have you researched them as an adult?

VG: I’ve been writing poems about Philippine life, culture, history, etc., for at least 40 years, if not longer. I wrote my first aswang poem (the aswang is a mythical Philippine monster) around 1986, when I was pursuing an MFA in Poetry Writing at Indiana University. I didn’t hear about the aswang from my parents but I’m sure I must have heard about them from my cousins. Certainly, aswang tales are very common in Philippine culture. I began to do research on the aswang when I was in grad school. I found that the mythology and folklore focused on the aswang only as monsters and I wondered about their inner lives as people, monsters though they may be. In 2016, I started writing about two aswang lovers, who pass themselves off as ordinary humans during the day but do their monster thing at night. This project turned into a novel in poems about the family life of these two people and their son. A couple of aswang poems that did not fit into the novel appear in Dragons & Rayguns. Incidentally, the aswang novel in poems is complete and I’m seeking a publisher for that book right now. There are also a couple poems in the book about Bakunawa, the Philippine sea dragon. Philippine myth tells us that there were once seven moons in the sky and Bakunawa ate six of them until people figured out how to prevent him from eating the last one, the single moon we still have, which coincidentally is a full moon—supermoon and blue moon—as I write this. Good thing Bakunawa didn’t eat this one!

JO: Is there any other question I should have asked you but didn’t? I was going to ask you about how it feels to be retired, but then I realized that that is probably only really going to kick in when classes start up again.

VG: I suppose a question might be “What other elements influenced Dragons & Rayguns?” Besides science fiction, pop culture is an important element: Doctor Who (or more particularly the Doctor Who universe), Frankenstein, Marvin the Martian, even Jimi Hendrix. Another element would be science itself, apart from science fiction. For example, I have a poem about xenobots, the first artificial creature or organism, created in a Petri dish, so to speak. There’s also a poem about ‘Oumuamua, the first known interstellar object detected passing through the solar system, which some experts initially suggested could be an alien spaceship. About retirement, the first of June was when I retired so it’s still pretty new, and as I write this my former colleagues at the University of Northern Iowa are probably working on their course syllabi at this moment [Ed. note: yes, at this very moment] since the first day of class is in less than a week. I’m happy not to be doing that, though I’m sure I’ll miss teaching quite a lot. I’ve been having stressful teaching dreams for a couple weeks now, like being unable to find my classroom on the first day or being in class and not knowing what the subject of the class is. I’m realizing this must have happened every August for many years, though I didn’t really notice a pattern before because I just took it all in stride. I just want to tell the dream machine in my head, “Stop! We’re not doing teaching any more!”

Thanks for this interview, Jim. And thanks for being a champion of my poetry for so long. This is the third collection of mine you’ve published and I’m very grateful.

Sunday, 11 August 2024

Fall 2024 FTRS Slate

Thursday, August 29

Vince Gotera

Iowa’s Poet Laureate will return to FTRS to launch his new collection of speculative poetry, Dragons & Rayguns (Final Thursday Press).

Thursday, September 26

Marc Dickinson

Dickinson, a UNI English alumni, is the author of the new short story collection, Replacement Parts (Atmosphere Press)

Thursday, October 31

A Night of Monsters

**this special event starts at 7:00. No open mic tonight.

For this special Halloween event, UNI’s Brooke Wonders, alongside students in her horror literature course, will be reading new stories of terror and dread.

Thursday, November 21

The Cities of the Plains

**one week early due to Thanksgiving

The Cities of the Plains: An Anthology of Iowa Artists and Poets features 57 artists and poets and highlights the immense talent of the state. Editor Paul Brooke will be joined by regional contributors to the collection.

Monday, 17 June 2024

GIVEN DAYS Coming This Summer!

Given Days by Amy Woschek Schmidt

NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDER!

Final Thursday Press is excited to announce our next project (and to reveal the book cover!). Given Days is an insightful collection of seasonally-based poems by Amy Woschek Schmidt. With a voice intimately attuned to the rhythms of rural life, Schmidt finds transcendence in the details of everyday experience. Whether celebrating the first blooms of spring, the fertility of summer, the turning of autumn, or the stillness of winter, Schmidt reminds us to be patient and to pay attention to the small miracles unfolding all around us.

Given Days, with an original cover illustration by Gary Kelley, is now available for pre-order directly from Final Thursday Press. It will be released later this summer.

Sunday, 7 April 2024

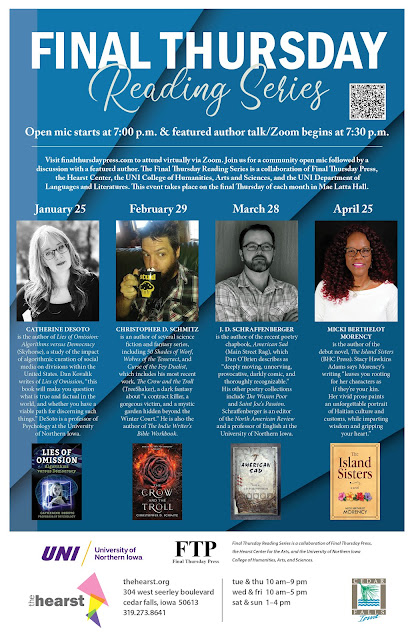

An Interview with Micki Berthelot Morency

The Final Thursday Reading Series takes place on April 25 at the Hearst Center for the Arts in Cedar Falls, Iowa. There will be an open mic at 7:00 p.m. (bring your best five minutes of original creative writing). Micki Berthelot Morency takes the stage at 7:30. The featured reading will also be simulcast on Zoom. Click HERE to register for a link.

Interview conducted by Olivia Brunsting.

OB: Why did you pick Haiti, Guam and St Thomas as settings in the book?

MBM: I was born in Haiti, so it’s my culture, and I wanted to portray the roles of women in that particular period in the country’s history in the book. I had the privilege of living on the islands of Guam and St. Thomas for some months, and I loved the people and the topography of both islands. I wanted to share some of it with the reader.

MBM: I was inspired by the strength of the women who raised me: my centenarian grandmother, my mother, my aunties and all the Haitian women I grew up watching as they struggled to overcome a culture that condemned them when they came out of the womb a female. I wrote the book to give voice to all the women who told me, “No one cares.” I wanted to show them that some of us see and hear them, that we do care. I want the takeaway for readers to be that life is messy, that we do the best we can with what we have, and that our culture influences everything we do, so we all need an open mind to understand “others.”

MBM: Like the characters in The Island Sisters, I knew that higher education was going to allow me to be self-sufficient, thus having control over my life. It was hard to assimilate. I’ve encountered many obstacles, but I persevered because I didn’t allow myself the option to quit. Most immigrants like me leave their home countries with concrete goals, so they work hard to make them happen. After college I worked in the banking industry, but I found my calling in the social service sector. I’m an advocate for women and children. My work at the shelter was the most rewarding for me because I could see how I’d impacted lives with measurable results. I wrote the book for those women as well.

OB: Without giving too much away, self-love is an important part of the book. What advice would you give to people who are struggling with self-love?

MBM: That self-love is not selfish. Once I learned to love myself, I experienced an abundance of love that I was able to share freely with others. People love their children, their romantic partner, their siblings…women seem to be wired to love everyone, and they leave themselves for las,t and by then the well is empty. Fatigue, stress, unmet needs, and expectations turn to self-loathing, and they buy into the belief that they don’t deserve love. My advice is start with yourself. Love all of you, and you will have plenty left for everyone else.

Wednesday, 13 March 2024

An Interview with J. D. Schraffenberger

The Final Thursday Reading Series takes place on March 28 at the Hearst Center for the Arts in Cedar Falls, Iowa. There will be an open mic at 7:00 p.m. (bring your best five minutes of original creative writing). J. D. Schraffenberger takes the stage at 7:30. The featured reading will also be simulcast on Zoom. Click HERE to register for a link.

Interview conducted by Tomiisin Ilesanmi.

In my case, I think I was drawn to writing poetry early on because it allowed me to be playful. I grew up in a working class home. We lived paycheck to paycheck. Playing sports was more important than reading books. And yet, it was also a home in which humor, irony, wordplay, and linguistic cleverness of all kinds was valued. When we learn to write in other modes and genres (namely expository prose), it’s usually for the sake of clearly communicating some pre-existing message. Maybe we want to explain something, argue a point, convince someone you’re right. The virtues in these modes are (usually) clarity, focus, and organization. But poetry sidesteps these imperatives. You can write a poem for the sheer pleasure of the feeling of words in your mouth. Knowing this origin story of my own journey as an artist might not illuminate my work, but perhaps the reader will understand at the very least that my poems look askance at the virtues of expository prose—and sometimes they do much worse than that.

TI: Poets are very particular about every word, line structure, or punctuation that goes into their work. As an editor yourself, how do you juggle the editorial and poet hat when writing? How has being an editor influenced your writing?

Tuesday, 20 February 2024

An Interview with Christopher D. Schmitz

The Final Thursday Reading Series takes place on February 29 at the Hearst Center for the Arts in Cedar Falls, Iowa. There will be an open mic at 7:00 p.m. (bring your best five minutes of original creative writing). Christopher D. Schmitz takes the stage at 7:30. The featured reading will also be simulcast on Zoom. Click HERE to register for a link.

Interview conducted by Jim O’Loughlin.

JO: You’ve also carved out a writing career in which you are heavily involved in publishing and promoting your books. Can you talk about how you think of your work as a writer/publisher?

Sunday, 21 January 2024

An Interview with Catherine DeSoto

The Final Thursday Reading Series takes place on January 25 at the Hearst Center for the Arts in Cedar Falls, Iowa. There will be an open mic at 7:00 p.m. (bring your best five minutes of original creative writing). Catherine DeSoto takes the stage at 7:30. The featured reading will also be simulcast on Zoom. Click HERE to register for a link.

Interview conducted by Jim O’Loughlin

CATHERINE DESOTO: My background in neuroscience and psychology allows me to characterize what is happening in the brain when one receives certain kinds of information, and then link this to social psychology research on preferring agreement over disagreement. In all, this makes our little pocket gadgets, and the way they work with the background algorithm, the perfect storm for increasing polarization. There is actually a lot of relevant research and knowledge that explains why society is splitting. Basically, human beings have a powerful innate love to be right; it is hardwired in the brain, and this allows us to understand the addictive nature of modern social media.

JO: While you are concerned about the effect of social media on individuals, the subtitle of this book—"Algorithms versus Democracy"— also points to your concerns of the political impact of these developments. What can be done to stop the corrosive impact on our politics?

JO: How, if at all, has writing this book affected your own use of social media? Do you do anything differently after spending so much time on this subject?

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)