Anne Myles is Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Northern Iowa and received an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her poems have appeared in On the Seawall, Whale Road Review, Lavender Review, Ekphrastic Review and numerous other journals. She currently lives in Greensboro, North Carolina. Learn more at annemyles.com.

Myles’s new chapbook What Woman That Was: Poems for Mary Dyer will launch on August 25 at the first Final Thursday Reading Series event of the season. Join us in the beautiful Hearst Sculpture Garden (rain location: Mae Latta Hall) for an open mic at 7:00 and Anne Myles at 7:30. Myles’s reading will also be simulcast on Zoom. Click HERE to register for a Zoom link. Pre-orders of What Woman That Was are available directly from Final Thursday Press and via Amazon.com.

Interview by Jim O’Loughlin

JIM O'LOUGHLIN: Who was Mary Dyer and how did you first become interested in her?

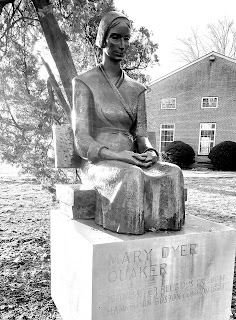

ANNE MYLES: Mary Barrett Dyer, born around 1611, grew up in England and came to Boston with her husband and first surviving child in 1635. Her story has several distinct acts. She was a follower of the lay spiritual teacher Anne Hutchinson, and along with other followers her family was sentenced to banishment from Massachusetts in 1637. In 1638, when Hutchinson was excommunicated from the Boston church, Dyer drew public attention when she followed Hutchinson out of the meetinghouse, and it was revealed that she had had a deformed stillbirth, a so-called “monster,” with Hutchinson as one of her midwives. Around 1651, after living in Newport, Rhode Island for a number of years, Mary Dyer left her husband and six children behind and went to England alone, where she stayed for six years. In 1657 she returned to New England as a Quaker. She was repeatedly imprisoned as she violated the anti-Quaker laws of Massachusetts and other colonies. This ultimately led to her being taken to the scaffold twice – first in 1659, when she was reprieved at the last minute, then in 1660, when she was in fact hanged. She was the only woman among the four Quakers hanged in Massachusetts in 1659-1661, whom Quakers refer to as the New England Martyrs.

As someone who was active as a Quaker in my early adulthood, and as a scholar of early American dissent, I knew who Mary Dyer was. But somehow it was only around 1999 when the story of her following Anne Hutchinson out of the church really hit me. A woman’s radical act of loyalty to another woman: there is nothing else like it in the records of that time. I saw it as an act of love, and it resonated with my own devotion to an older woman who had been an important guide to me, and whom I lost, as Dyer ultimately lost Hutchinson. From that moment I was driven to write about Dyer, to claim her as someone I intuitively understood. She became my personal doorway into the early American past.

AM: I’ve always believed that scholarship encodes deeply personal concerns, at least in terms of what we are drawn to study, and I’d articulated some of the private reasons for my interest in Dyer in my academic writing. But around 2017 I realized that I needed to write truthfully about my life without the distancing of an academic approach – and I saw nearly simultaneously that the way I could start to do this was to interweave my life with Dyer’s much more interesting one. That started out as a hybrid memoir project, which I worked on for about a year. But somehow the singular narrative trajectory – her life moving inevitably towards her death, while mine was moving towards what? – became problematic. When in 2018 I transitioned back to poetry, my original creative form in my earlier life, I realized how freeing it was. I could write multiple poems, multiple truths, multiple perspectives, as I explored Dyer’s life and my feelings about it. (I write directly about my life in poems outside this project.) Beyond providing a fluid way for me to consider Mary Dyer, my poems about her, many of them written during my MFA studies, became a rich field for exploring different lyric styles and strategies of address.

JO: A number of the poems in this collection are “persona poems,” written from the perspective of Dyer. How did you decide to take that approach? What were the challenges in finding the language to represent her immediate experience?

AM: Persona poetry about real or imagined historical figures is a very popular mode in recent years– book-length collections included. So it seemed an obvious approach to try. But the first attempts were terrifying to me as a scholar! Up to that point I had always carefully written about Dyer from the outside, marking the distance of my own subject position, as academics say, and making clear when I was speculating without textual evidence. To enter into her imaginatively and make stuff up felt really transgressive – I felt like they would revoke my PhD! But of course the transgression felt thrilling and freeing too. Yet even now it makes me a little queasy . . . I think the book most people would have written about Dyer would be all persona poetry. But I couldn’t do that; ultimately I am less drawn to historical fiction as a mode and more drawn to writing about and around what is known about her, while still speaking as myself.

I never struggled with finding a voice for Mary–that was always fun. I think many years of immersion in seventeenth-century discourse and my love of early Quaker thought and writing made it come naturally to me. I wanted her to speak in terms she would have known, and in a voice that evoked her period without being cloyingly archaic. I feel a resistance to persona poems where the characters “talk in poetry” or think like contemporary subjects. I guess that’s the scholar in me still.

JO: Some of my favorite poems in the book are the ones that directly address both the connection you feel to Dyer and the historical and ideological distance that separates you. Those poems made me wonder what you feel you learned about Dyer (and maybe about yourself) during the process of writing this book.

AM: What an interesting question! I had reflected on Dyer and the grounds of my identification with her so long, it’s hard to say what I learned about connection and distance during the actual writing of the poems. What I learned, I think, is how essential it is to me to keep articulating that nexus – that the issues of how we long for the past, how we seek connection to it, how the dead look back at us resistantly when we look at them are all a key part of my material and my distinctive style as a poet interested in history. I’ve now drawn on this perspective writing about other figures as well. A big moment was when I came upon the approach of addressing Dyer directly; I’d say this became my favorite way of writing about her, since it allowed me to put the problems of relationship right up front.

Yet I suppose I did learn a lot about Dyer’s life, specifically through imagining parts of it that aren’t in the record. The Dyer I’ve created feels very real to me now; I sometimes have to remind myself that she is a product of my own mind! I feel closest to her when I summon her embodied experience. Whatever our ideological differences, I know what a stone ledge felt like against her arms; I know at some point her nose dripped when she leaned forward in her kitchen garden.

JO: Why do you want other people to know about Dyer? In what ways do you regard her as a significant figure in the present?

AM: The story of Dyer’s life–her courage, her agency, her allegiance to those she chose as her people–is remarkable, inspiring, perhaps confounding in any era. Though she is a venerated figure among Quakers, and known to those who study early New England, I want everyone to hear about her. But she has resonated for me at a new level in the years since 2016. Her persistence in witnessing against injustice seems incredibly relevant. As a high-status woman in her society (note that she was always “Mistress Dyer,” the elite designation, never “Goodwife Dyer”), she found powerful ways to deploy her privilege, to make an impact with it, even if her choices led to her death. I realize too how much the struggles she was involved in speak to border politics in the present: who is allowed into a colony or country? What is the penalty for violating the law? And as I’ve grown older, the fact that Dyer was herself what we would call middle-aged (she was about 49 when she died) has also felt important. Celebrating the older woman as heroine, as someone actively determining the course of her life, is moving and meaningful to me.

No comments:

Post a Comment